Harvest Moon – Expedition Karakoram

A new alpine-style route on Dansam West (6,600m), rising above Pakistan’s remote Kondus Valley in the Karakoram. The 1,600m line, graded M6 WI6, weaves up compact granite and ephemeral ice to the mountain’s western summit.

24 Hours to Islamabad: A High-Stakes Ride on the Karakoram Highway

We’ve been sitting in a cab for more than 12 hours and we still have 12 hours more before we reach Islamabad. It’s been dark for three hours now, and the abyss above which we drive is hidden. A clock below an “inchallah” sticker reads eleven o’clock. Our driver is showing symptoms of fatigue. He rbs his eyes incessantly and his head drops forward in a weightless way. I try to put my seat belt on, but this option has been previously removed from the car- probably for making something more practical. Jerome attempts to do the same, in turn failing, and we look at each other with panic-stricken faces.

With tenderness, I put my hand on his leg and tell him: “dear, we are going to live the most dangerous moment of our Pakistani adventure”. The “Bollywood techno” music blares on the speakers. An annoying girl screams “I love you habibi” over and over. We sink into a submissive silence. Although the fatigue due to reaching the summit of Dansam Peak West a mere 4 days ago is drawing our eyelids shut, the rugged road and the terror inspiring fact that our driver is going for a 24h sleepless “go fast” to Islamabad keeps us awake, in a state of panicked stupor.

The Karakorum highway is a hellish road linking Islamabad with China. It is the only means of communication between the Pakistani capital and Skardu. In case of bad weather, and because planes flying around Nanga Parbat are not equipped with modern gps systems, the only travel option is driving 650 strenuous kms separating the two cities. Rather than a transport route, this option resembles more a game of Tetris- obstacles include overflowing rivers, cattle slalom, and the spicy game of overtaking other cars with the edge of a cliff only centimeters away. In short, I do not recommend this option to anyone who suffers from vertigo, or who may be car sick. In our case spring avalanches have cut off the highway, forcing us to detour along a longer and scarier road…

This is my third time visiting this country. I would come back every year if I could. The mountains are like vast forests of towering granite needles, and above all the Balti folk are uncommonly friendly and have a surprising sense of humor. I have always felt welcome here. Their sense of hospitality is strange to us Europeans- a tradition long lost. Most of all, it is the hours spent talking with my good friends and Hushe mountaineering legends Little Karim and Hassan Jan that bring me back. This is why I brave the dangers of the Karakoram roads, to visit the incredible country of Baltistan, to climb its mountains and meet its inhabitants: The Last Pure Men.

Jerome’s Email and the Mountain of Imagination

Let me go back to the beginning. In February 2021, in the midst of the Covid crisis and with political hostilities between France and Pakistan at their highest, with our mountain guide work cut down to a trickle and our income reduced by 60%, it is precisely at this moment, in the midst of global chaos, that my phone rings. On the other side it’s the voice of the incombustible and ever motivated Jerome Sullivan, a great friend and a frequent companion of many great adventures. Together we have drunk unfathomable quantities of red wine and shared many hours sipping Argentinian “mate” around a “Magallanica” stove in remote Patagonia. Excited, he encourages me to open my email and to look at a photo he has sent.

It shows the upper third of a mountain. The shot is taken from so far away that it is impossible to zoom in without transforming the photo into a jumble of big boxy pixels. These kind of vague photos are my favorite, because they leave so much room to imagine what the mountains may be like. Jerome knows this, and I suspect he’s made a conscious choice with the intention of motivating me into coming. He tells me the photo was taken by the American alpinist Steve Svenson from the top of Link Sar, looking twoards K 13, A.K.A Dansam Peak. An unclimbed mountain he tells me, with an estimated height of 6,666m. Very little information… Many teams have asked the Pakistani ministry of tourism for the permit, but none have been granted permission.

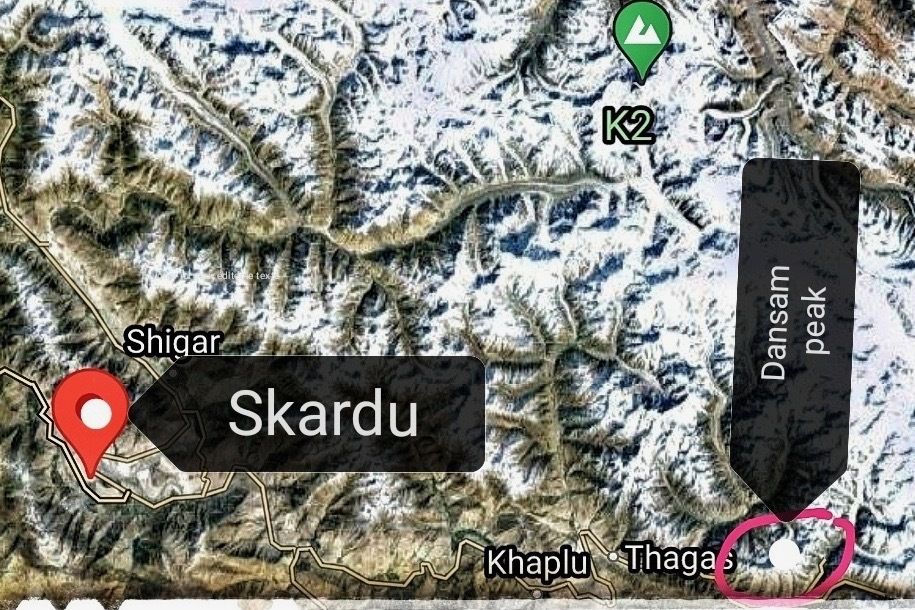

Some quick research reveals the Dansam massif is composed of three main summits, the main peak and the western and eastern summits, which are only 50 or so meters lower. This massif has been closed to tourism since the 80’s because of the war with India. The highest war in the world takes place at more than 5000m altitude, on the Siachen Glacier, only a few kilometers away from the Dansam range. The dispute broke out after the Second World War when England deserted its colonies and India and Pakistan began a long quarrel over a land called Kashmir. Recently a cease fire has been called, and for the last two years the Kondus valley, where our objective is located, has been opened to foreign expeditions.

Although the photo Jerome sent is just a blurry image of a faraway mountain, it is enough to encourage me to meet the rest of the team. Victor Saucede, Jeremy Stagnetto, Jerome Sullivan and myself. Never in history, since my favorite Argentinian band “the Luthiers” got together, has such a team existed. I cannot refuse the call!

I have had the good fortune to travel with Jeremy several times. He is attentive and very funny- essential qualities for an expedition partner. His virtues as a climber are so numerous I won’t even bother to mention them here. His aptitude for extreme effort is unmatched. Victor is a young man from the Pyrenees we recently met in Vallorcine. His kindness is rivaled only by his grace on vertical terrain. As the famous French alpinist Yannick Seigneur said: you should always have a Pyrenean in your team. This time there will be 2 of us.

Departing during a global pandemic might be the toughest part of a Himalayan expedition. Last minute vaccine requirements, (failing) Covid tests, two flight cancelations and long weeks of battling with plane companies are all serious tests of our motivation. Yet we hold fast and our little crew of four negotiates through the logistical tempest. We finally managed to take off from Paris on May 28th. Two days later, under the blazing sun of Skardu and with the chant of the Muezzin syncopating our preparations, we excitedly pack up the yellow Hushe village bus to the brim and set out for the wild mountains of the Kondus valley.

Khor Kondus: Where the Map Ends and the Mountain Begins

Khor Kondus lies at the end of the dusty road. It’s Victor’s first time in Pakistan and by the time we reach the village, the window is greased up from his face squashed against it, trying to glimpse the top of the many towering rock monoliths. As we drive past the first houses, at dusk, the inhabitants are waiting for us. They are excited to see visitors, as it has been more than 20 years since a foreigner has come to the village. For many, except the elders, this is new. It is the sign that times are changing for the better; tourism is a good local source of income. First the children come to meet us, running behind the vehicle, snotty nosed and muddy, screaming wildly the few words of English they know.

As we set up camp, curious adults come to see who we are. We are delighted and share gestures, smiles and hugs. They are affectionate people and we feel welcome. Very soon we are surrounded by half of the village. Everyone laughs, gesticulates, and they tell us stories in Balti we do not understand. It doesn’t matter- communication is somehow fluid, no matter the language difference.

Among those who welcomed us in the evening are the porters who will help us take the gear to our Base Camp at circa 4000m, a place called Minguili by the locals. It is a summer grazing area for the yaks and it’s sparsely grassed pastures are a luxury in comparison with the arid and mineral surroundings.

Once base camp is installed, we begin to explore further up valley. Finally, the awaited moment arrives. The instant when we put a tangible form to the imaginary world we’ve created. Our mountain of vapor materializes- cold, brute, and mineral. For hours we’ve talked strategy, looked at maps and satellite images. We discussed the rock quality and the steepness by phone. So many months of envisioning the shimmering mountain hoping it will not be a mirage.

Now below the formidable barrier composed by the three summits we are ecstatic. Fractured hanging glaciers of a dark healthy blue are split by massive pillars of granite. Paper thin ridge lines are crowned with impossible looking snow mushrooms hanging dangerously over the edge . We watch in awe as the rumble of falling ice shakes the narrow valley, triggering a massive avalanche, filling the valley with a cloud of snow, and our souls with fear and excitement.

Breaking Through: The Headwall Question Mark

The main summit, our initial objective, seems too exposed to falling ice and we decide to climb the pillar that leads directly to the western summit. A compact granite prow, 1,600m long, scarred with a bone white ice smear that dead ends in the steep head wall. The line of my dreams: a logical route in the middle of an impossible wall.

It is with this line in mind we return to base camp only to be pinned down by successive storms. The long wait is difficult to bear as our time on the mountain is running thin. The thought of leaving without even attempting this masterpiece of alpinism is depressing. My calculations coincide with the Muslim calendar: the 24th of June is the full moon. I share the idea in our group that the change of moon can bring a change in the weather pattern. The farmers in my Spanish homeland of la Rioja often associate these two events and it seems to coincide with our weather forecaster’s latest messages. The team members quite like the idea and suggest combining this lunar event with sacrifices to the yak god. Surely the weather will give us a break!

On the 24th, with faith our strategy will pay off, we depart from our base camp in a flurry of snowflakes. By nightfall we reach advanced base camp at 5,000m.

The next morning, we set off for our 6 day ascent. After climbing 400m of zigzagging snow ramps and wading through terrible and inconsistent snow, we finally set up camp on a snow rib dubbed “les pentes à Djamel”, Djamel being Jeremy’s nickname. Here, we wait out the snowstorm that follows for the next 24h. It seems the yak gods are not fully satisfied with our sacrifices. Our line of ascent is a gully, and it channels the falling snow. Although our tent is not directly exposed, the snow aerosol caused by the frequent avalanches shakes the tent violently.

The next day we leave under a light snowfall and heavy spindrift. We are now in the central gully system and the ice quality is great. Between shouts of “spindrift!” and ‘hoods on!” we make good progress. Some pitches are quite steep and physical and others more moderate and harder on the calves. This ice gully leads us to another snow rib we call “le linceul” -a reference to the Grandes Jorasses. We arrive quite late in the night and dig out a poor bivy. The night is short, and on the 28,th at first light we are awake and ready for the big day.

Today we face the question mark in our line – we must breach the compact headwall and we need to find a flaw in its steepness. Above us, 400m of abrupt rock leads to the summit slopes. We make slow but unrelenting progress, discovering ephemeral ice smears on every pitch. Our line connects! Patches of ice allow us to keep good pace in otherwise unclimbable terrain. Victor leads the most memorable pitch: an improbable ice smear pasted though an overhanging dihedral. We declare that, sadly, at only 26 years old, Victor has nothing to look forward to. He has just climbed what could be the best pitch of his life! The ice has formed in the most improbable places thanks to the bad weather of the past weeks. As we will discover while descending the route, because of the rising temperatures, these good ice conditions are quite short-lived.

As night comes, we find an exposed cornice on a ridge at around 6000m. The main difficulties are behind us and we crash into our sleeping bags. We have high hopes of reaching the summit the next day!

Summit Surprise: The Piton and the Pillar

On the 29th, we woke to a starry sky. Fatigue weighed heavily on us, making every movement sluggish. Breaking camp was an effort in itself, but as dawn approached, we left behind our tents and rock gear and set off for the summit.

We expected the remaining ground to be straightforward—moderate slopes we would dispatch quickly. Reality had other plans. Beneath a deceptive layer of powder snow, bullet-hard ice turned every step into an exhausting battle. On 60-degree slopes, we were forced to build anchors to protect each pitch. The 400 vertical meters that separated us from the summit consumed the better part of the day, sapping our energy as the hours slipped by.

As we neared the top, we received our second surprise. The west summit, a small rock nipple hidden until the last moment, finally revealed itself. Martin, leading the final stretch, suddenly burst into laughter. Expecting some new obstacle barring our way, I hurried up to join him—only to see the cause of his amusement. Dangling from an old piton was a fixed rope, swaying gently in the wind.

We all broke into laughter at the absurdity of it. After all the effort, the uncertainty, and the commitment of opening a new line, here we were, twenty meters from the summit, face to face with a relic of a previous ascent. In truth, we didn’t care much about whether we were the first to stand on this particular summit. But finding that piton at the very end of such an intense journey struck us as comical, even surreal. It sparked reflections on the nature of climbing—how the value of a route lies not in its ‘first ascent’ status, but in the purity of the experience itself.

Our line up the north face had been untouched; we had pioneered a route with no traces of prior passage. The uncertainty, the doubt, the challenge—these were the elements that mattered most to us. As for the fixed rope, we could only speculate. It likely belonged to a Japanese team who, years before, might have reached the west summit via the south face’s snow slopes, coming from the still-restricted Goma flank. The presence of the rope, coupled with its heavy style, suggested a siege-like ascent. Yet on our slender pillar, we found no trace of anyone who had passed before us.

Standing on the summit, the discovery of that old rope did nothing to diminish our joy. If anything, it deepened it. Our climb had been an adventure into the unknown, and nothing could take that away from us.

Harvest Moon Descent

We descended from the summit in a day and a half, rappelling the same line we had climbed. On the evening of the 29th, tired but elated, we stumbled back into base camp. The feeling of having traced a pure, aesthetic line on such a wild and untouched face filled us with a deep sense of privilege. We named the route “Harvest Moon”, a nod to the lunar phase that had finally delivered the break in weather we needed for our ascent.

The next morning, there was little time to bask in the glow of success. We packed up base camp at first light and began the next leg of our adventure—racing to catch a flight from Islamabad with barely enough days left.

As we left, it was clear that the Kondus Valley holds countless treasures for future climbers. The villages of Khor Kondus and Karmanding are rare and special places, inhabited by people who endure incredibly harsh living conditions yet radiate kindness and hospitality. Their welcome was humbling, a poignant reminder of the human connections that enrich every expedition.

For alpinists seeking new lines, the valley’s surrounding granite spires offer endless potential. However, the rock quality can vary—what looks solid from afar may demand careful inspection up close. Regardless, the sheer scale and beauty of the landscape are undeniable. And when the climbing is done, a visit to the local hot springs is the perfect way to unwind sore muscles and reflect on the journey.

A heartfelt thanks to the Balti people, whose warmth and generosity left a lasting impression on us. Their spirit, much like the mountains that tower above their homes, is something extraordinary.